Introduction

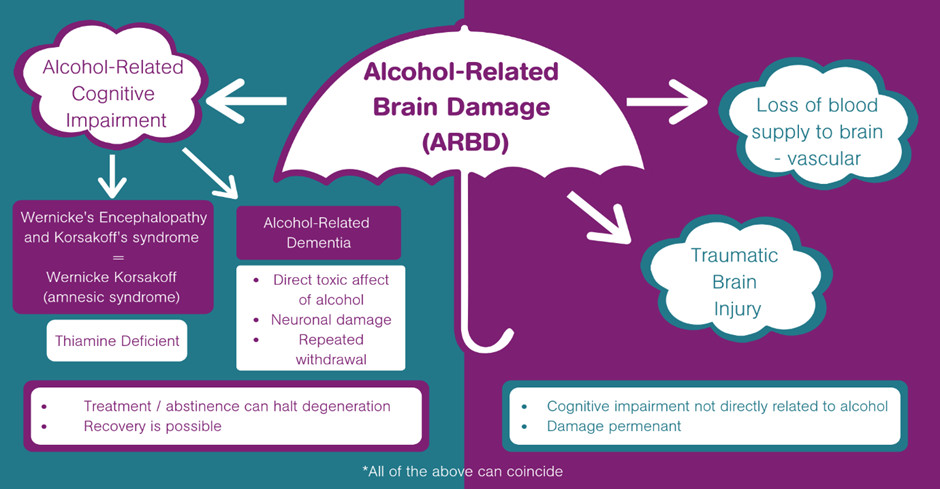

Alcohol-related brain damage (ARBD), or alcohol-related brain injury (ARBI), is an umbrella term for the damage that can happen to the brain as a result of long-term heavy alcohol consumption. ARBD can result from heavy episodic drinking, chronic heavy drinking and long-term moderate drinking. ARBD covers several brain disorders and conditions including Hepatic Encephalopathy, Alcohol Amnesic Syndrome, Wernicke’s Encephalopathy and Korsakoff’s Syndrome (International Classification of Diseases Statistical Manual, version 10, code F10.6). Some of these disorders are potentially reversible, while others are not, which makes early identification and beginning effective treatment important (Paterson & Schölin, 2021). ARBD also encompasses damage to the brain caused by alcohol withdrawal and recurrent head injuries also associated with chronic alcohol misuse.

This resource begins by describing current literature surrounding ARBD. We hope this will help you to understand what ARBD is, as well as recognise the common characteristics associated with the range of ARBD conditions. We also want to highlight the relationship between ARBD and homelessness, as well raise awareness around the complex, diverse and long-term care needs of those living with ARBD.

Heavy alcohol consumption causes structural and functional changes to the brain resulting in a broad range of both neurological and neurocognitive impairment. Those affected by ARBD often experience problems with cognitive, physical and emotional functioning. The frontal lobe of the brain is often affected by ARBD which results in difficulties with planning, decision making, inhibition, impulse control, abstract thinking and cognitive flexibility (adapting to situations, switching between tasks). Other cognitive effects of ARBD include memory problems, attentional difficulties and reduced information processing.

Below is a summary of common cognitive, physical and emotional changes associated with alcohol-related brain damage.

Cognitive

- Disorientation, confusion about time and place.

- Impaired attention and concentration.

- Information processing difficulties (verbal and visual)

- Confabulation, often as a means to fill in gaps in context and memory resulting in inaccurate accounts of recent events

- Apathy

- Impaired executive functions (impulse control, decision making, planning, problem solving, inhibition, cognitive flexibility)

Physical

- Ataxia – a gait disorder often resulting in poor balance

- Damaged liver, stomach and pancreas

- Possibility of traumatic brain injury reducing cognition further

- Peripheral neuropathy – numbness, pins and needles, burning sensations or pain in hands, feet and legs

- Malnourishment

Emotional

- Irritability

- Depression

- Reduced motivation

- Aggression

To understand how ARBD affects a person’s life, it’s important to consider the role which all of the above play in our day-to-day functioning and ability to live independently. Our cognition governs our ability to look after ourselves, look after other people, manage our responsibilities (e.g. employment, bills, housing), plan for the future and make decisions about our lives. For a person living with ARBD, the impairments it causes can make many aspects of day-to-day life incredibly challenging. Furthermore, the effects of ARBD limit a person’s ability to engage with alcohol support services, which often reduces the likelihood of them overcoming their alcohol problems and maintaining abstinence. These challenges become even greater for those who continue to drink without understanding the consequences and further harm it causes, often resulting in the need for intervention from health and social care services.

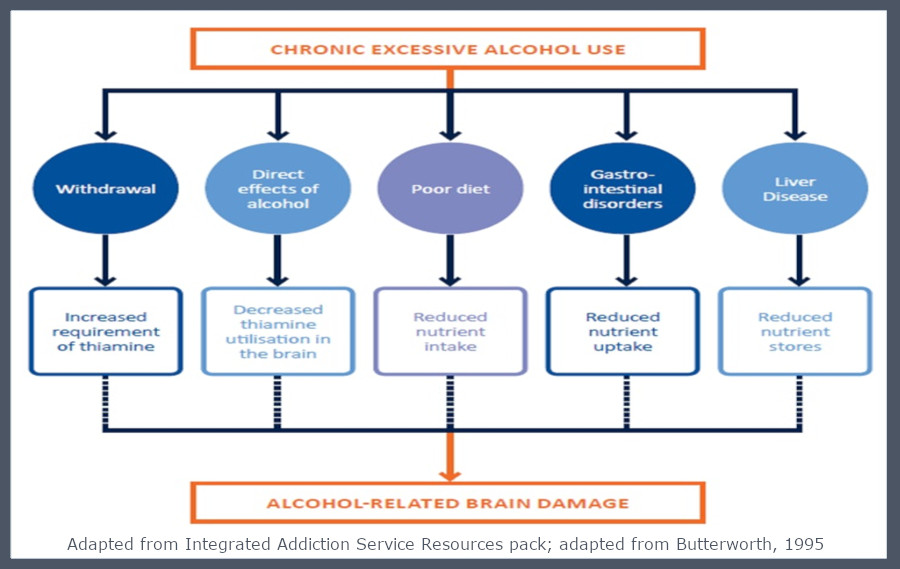

People who are diagnosed with ARBD are usually aged between 40 and 50 (Alzheimer’s Society, 2021). It is not clear why some people who drink too much alcohol develop ARBD, while others do not. The prevalence of ARBD is higher amongst men than women. However, women who have ARBD tend to get it at a younger age than men, and after fewer years of alcohol misuse. This is because women are at a greater risk of the damaging effects of alcohol. Despite the increasing incidence of ARBD in the UK in recent decades, it is currently under-diagnosed, managed inappropriately and treated inadequately (Horton et al, 2021). ARBD is not often recognised and research into the area is lacking. This means that the number of people living with ARBD is probably higher. Alcohol-related brain damage (ARBD) is primarily caused by chronic alcohol misuse and thiamine deficiency, and results in a broad range of impairments.

There are various statistics on how common ARBD is in the UK, although it is hard to get a totally clear picture. Around 10 million people in the UK regularly drink at above low-risk levels which means they drink more than 2 to 3 units a day or 14 units a week. In addition, 0.5% of the UK population have some changes in their brain as a result of their alcohol use, while 35% of the very heaviest drinkers are thought to have some form of ARBD. One of the most severe forms of ARBD, Wernicke-Korsakoff’s Syndrome, is seen in around 12% of dependent drinkers. As mentioned earlier, ARBD is not always limited to those with chronic alcohol problems. Many people waver between healthy and unhealthy alcohol use throughout their lives, and can experience alcohol related brain changes without forming a dependence. Alcohol sensitivity varies from person to person which means it can difficult to identify exactly how much alcohol use puts one at risk for ARBD.

It’s important to understand that ARBD is non-progressive if abstinence is maintained. No more alcohol means no more damage, therefore ARBD is not the same as having an intellectual disability or dementia. The damage caused by ARBD ranges from mild to very severe.

Wernicke’s Encephalopathy (WE)

Wernicke’s Encephalopathy (WE) is an acute, potentially reversible neurological disorder caused by a deficiency in or severe depletion of thiamine (vitamin B1) that can result from chronic alcoholism and poor nutrition (Zahr et al, 2021). Those who drink heavily are at a high risk of thiamine deficiency because of the poor diet associated with their lifestyle, and the fact that chronic alcoholism compromises thiamine absorption from the gastro intestinal tract, limiting the body’s ability to store and use thiamine. If WE is recognized early, treatment with thiamine can result in rapid clinical improvement. However, if WE remains undiagnosed and untreated, 80% of patients with this condition develop Wernicke’s Korsakoff’s Syndrome (WKS), a severe, typically permanent neurological disorder characterized by anterograde amnesia. The term Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome (WKS) is used to describe the range of brain and behavioural impairments associated with thiamine deficiency.

WE is characterized by a combination of ocular motor abnormalities, cerebellar dysfunction, and altered mental state (Victor et al, 1994). Ocular motor abnormalities in patients with WE may include nystagmus (repetitive/involuntary movement of the eyes) or ophthalmo plegia (paralysis of the muscles controlling eye movements). Cerebella dysfunction manifests as loss of equilibrium, incoordination of gait, trunk ataxia, dysdiadochokinesia and, occasionally, limb ataxia or dysarthria. Approximately 80% of patients with WE exhibit an altered mental state, which may comprise mental sluggishness, apathy, impaired awareness of an immediate situation, an inability to concentrate, confusion or agitation, hallucinations, behavioural disturbances mimicking an acute psychotic disorder, or coma.

Wernicke’s Korakoff’s Syndrome (WKS)

Wernicke’s Korsakoff’s Syndrome (WKS) is a form of ARBD caused by thiamine deficiency that most commonly occurs in chronic alcohol use. It is characterised by severe difficulties with short-term memory and learning, as well as problems with balance and eye movements. Unlike other forms of ARBD, the cognitive effects of WKS are irreversible. Confabulation is another common feature of WKS, where individuals create false memories but without the intention of doing so. The memory changes caused by WKS often result in a person’s memories getting mixed up or having “gaps”, which are then filled resulting in inaccurate memories. This is commonly known as confabulation. These memories are often driven by a person’s need to make sense of their own situation. Problems with visuospatial skills, eye movements and coordination are also commonly observed in individuals with WKS. A person’s general intellect and verbal abilities often remain intact following WKS, which can lead to difficulties with clinical diagnosis (e.g. ability to mask symptoms) and potential overestimation of cognitive ability and capacity by clinicians.

Alcohol-related Dementia

Alcohol-related ‘dementia’ is another form of alcohol-related brain damage (ARBD) which results from shrinkage to the frontal lobes and cerebellum. Alcohol-related dementia is characterised by difficulties with memory, planning, changes to personality, reduced social functioning, problems with balance/coordination, attentional difficulties and impulsivity dementia. The combination of these difficulties significantly impacts a person’s ability to function day-to-day. The person may have memory loss and difficulty thinking things through. They may have problems with more complex tasks, such as managing their finances. Damage to the part of the brain that controls balance, co-ordination and posture means that a person with alcohol-related dementia may be unsteady on their feet and more likely to fall over – even when they are sober. Apathy, depression or irritability are also common which can make it even harder for the person to stop drinking, as well as create barriers for people close to them to help. It is currently unclear as to whether alcohol has a direct toxic effect on the brain cells, or whether the damage is due to lack of thiamine, vitamin B1. Nutritional problems, which often accompany chronic alcohol misuse are also thought to be a contributing factor.

ARBD & Homelessness

Alcohol misuse is both a cause and effect of homelessness (Shelter 2007). Previous research has highlighted the major health risks posed to the homeless population as a result of alcohol abuse and dependence (Gilchrist & Morrison, 2005). Homelessness is increasing in England and across the UK. It is estimated that 10% of the population in the UK have been homeless at some point in their lifetime (Crisis 2014) and there were 2,440 rough sleepers identified in England in 2021 (Department for Levelling Up, Housing & Communities, 2021).

Over half of homeless people drink hazardously, but the extent of alcohol related brain damage is not known (Gilchrist & Morrison, 2005). Previous research shows people who are both homeless and have addictions face further difficulties in finding housing, accessing mental health support and overcoming their substance use (McQuistion et al 2014; Padgett et al 2008). This is due to stigma associated with homelessness and substance misuse (Phillips 2015), low levels of social support (Velasquez 2000; McQuistion et al 2014) and the prevalence of alcohol-related brain damage.

Homelessness affects individuals of all ages, genders, and ethnicities. We often consider homelessness to be a result of poverty, lack of housing or government support, and socio-economic challenges however, homelessness can also be caused by issues related to trauma, mental health, learning disability, alcohol and substance dependence, and other social and behavioural problems (Glasser, 1994). It has become more widely understood that there is often a continuum, and constant interaction, across several of the causes listed above (Anderson, 2001) (Anderson, 2007) (Forrest, 1999). People experiencing homelessness are likely to have additional needs around their mental and emotional wellbeing (Homeless Link, 2017). A study conducted by Homeless Link (2017) found 80% of homeless respondents reported experiencing a mental health issue. Of these 45% reported having a diagnosis, which compares to 25% of people within the general population.

Despite the prevalence of mental health needs amongst the homeless population, all too often these we see these people “slip through the gaps” in mental health services. If left untreated, poor mental health – often stemming from experiences such as childhood or adult trauma, family breakdown or bereavement – can result in a vicious cycle, maintaining and exacerbating a person’s experience of homelessness. There is lots of research which suggests a strong correlation between mental illness and homelessness. It’s important to remember that one of them can be responsible for the other. The disastrous results of having a mental illness can make it difficult to hold on to home or family. On the other hand, the long-term absence of adequate shelter and the consequent difficulties can cause deterioration of mental health.

Trauma & homelessness

A significant factor contributing to the mental health needs of the homeless population is trauma. Research has shown that people who are homeless are likely to have experienced some form of trauma, often in childhood (E.Sundin and T. Baguley, 2015). A significant proportion of those under criminal justice, substance misuse and homelessness services have experienced trauma as children (Lankelly Chase Foundation, 2015).

Trauma generally refers to experiences or events that by definition are out of the ordinary in terms of their overwhelming nature. They are also more than stressful – they are shocking, terrifying and devastating to the trauma survivor – and often result in feelings of terror, fear, shame, helplessness and powerlessness. It’s important to understand that trauma impacts the entire person. Traumatic experiences influence how we think, how we learn, the way we remember things, the way we feel about ourselves, the way feel about other people and how we make sense of the world.

There are three types of trauma:

- Type 1 trauma occurs at a particular time and place and is short-lived, such as a serious accident, sudden loss of a parent or a single sexual assault.

- Type 2 trauma refers to events which are typically chronic, begin in early childhood and occur within the family or social environment. They are usually repetitive and prolonged, involve direct or witnessing of harm or neglect by caregivers or other entrusted adults in an environment where escape is impossible (FEANTSA, 2017a)

- Vicarious trauma – This describes trauma which can come from hearing someone else’s trauma.

Furthermore, homelessness itself can lead to further trauma. The loss of a home is often accompanied by loss of community, possessions, and security, as well as feelings of loneliness, despair, fear, and dread. People who experience trauma are likely to have problems sustaining stable relationships due to their history. Individuals are more likely to have feelings of shame and lack trust in others which can have an impact on how they engage in relationships that are there to help and support. They are also more likely to experience overwhelming levels of stress, have difficulties regulating emotions, and may have other mental health needs such as depression and anxiety.

Whilst homeless, a person be victim or witness of an attack, sexual assault or any other violent event. People can also be re-traumatised by services that leave them feeling powerless and controlled; for example, if they lack privacy and are being challenged in demanding ways (FEANTSA, 2017). For many of the reasons listed above, it is hardly surprising why people may choose to cope with these experiences through unhealthy ways including self-harm, drugs or alcohol.

The homeless population is diverse and includes people with different level of support needs. Most people who become homeless due to housing shortage or job loss need little support and can quickly return to housing. Those who become homeless for different reasons, often due to addiction, mental health or system failures, such as absence of social care or prison, are more likely to remain homeless for a longer period and have complex and interrelated support needs. Those who are long –term (or chronic) homeless and cycle between street, psychiatry, criminal justice services and temporary accommodation have the greatest support needs and are the most likely to have been exposed to trauma.

Many people who are at risk of or are experiencing long term homelessness have been exposed to trauma. Unfortunately, current services and support systems are not always equipped with the necessary tools or the right responses to help people who have a history of trauma. Often this lack of understanding limits the effectiveness of homeless services. Unaddressed trauma is common amongst homeless people; however, many have been unable to access appropriate treatment and support due to the prevalence of substance misuse or alcohol difficulties, as well as the rigid nature of statutory mental health and drug/alcohol services. This problem is often worsened by stigma and unhelpful narratives which society holds towards homeless people. Without appropriate treatment and support, individuals who have experienced trauma and homelessness are at increased risk of the following:

- Difficulties with interpersonal relationships

- Family discord, separation, and divorce

- Insomnia or hypersomnia

- Job loss and chronic unemployment

- Misusing alcohol and/or other drugs

- Mental health disorders

- Social withdrawal and isolation

- Self-harm

- Suicide

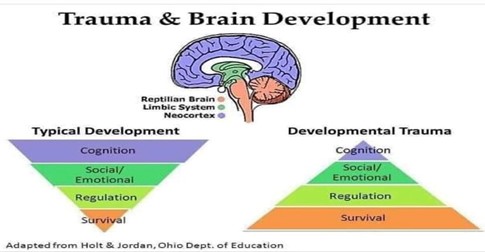

Research has highlighted the impact of traumatic experiences on neurocognitive and emotional functioning/development, particularly when they occur in childhood. Below is a summary of common behavioural, physical, cognitive and psychosocial effects associated with trauma.

Behavioural effects of trauma

- Difficulties establishing and maintaining relationship.

- Misuse of alcohol and/or other drugs

- Acting in a risky, reckless or otherwise dangerous manner.

- Self-harm.

Physical effects of trauma

- Disrupted sleep

- Suppressed or heightened appetite

- Increased vulnerability to physical health problems (e.g. long-term chronic illness)

- Hyperarousal

Cognitive effects of trauma

- Problems with concentration or focus.

- Flashbacks (re-experiencing the trauma).

- Nightmares or night terrors.

- Dissociation

- Panic attacks

- Memory problems

Psychosocial effects of trauma

- Agitation and irritability

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Emotional dysregulation

- Low self-esteem/feelings of worthlessness

- Inability to experience pleasure

- Suicidal ideation

The image below lays out a typical developing brain versus a brain affected by trauma. The brain may develop in a survival mode and the individual may experience difficulty regulating emotions, forming relationships or attachments and delays in cognition.

Complex trauma very often results from adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). ACEs refer to experiences during childhood that are considered maltreatment, for instance sexual, physical, emotional or neglect. Such events are neither ordinary, nor uncommon. Destructive events, such as natural disasters, are easier to accept than atrocities committed by fellow human beings. There is a lot of denial, repression both at societal level and at the individual level about traumatic events. ACEs can also stem from living with an adult with mental illness, substance abuse problems or criminality or if domestic violence is committed in the household.

ACEs have long lasting impact, especially because they happen in a developmentally vulnerable period in a person’s life. The earlier in life trauma occurs, the more damaging the consequences are likely to be. During childhood, traumatic events impair the biological regulatory systems and their normal attachment systems, especially if the perpetrator is a person whom they trusted and had strong emotional ties with.

Difficulties with interpersonal relationships often stem from attachment difficulties in childhood. Appropriate attachment experiences occur in childhood and influences our ability to securely relate to others throughout life. Therefore, if the ongoing traumatic experience occurs within the context of a care relationship (for example, a parent or caregiver may be abusive, neglectful or unpredictable), insecure attachments are likely to develop. Those who develop insecure attachments may grow up believing that others will always hurt them, leave them or both. These experiences may then continue into adult life, making relationships with others difficult to.

Trauma, ARBD & engagement with support

There is a clear link between traumatic experience and maladaptive behaviours such as: problematic drug and alcohol use, engaging in risky behaviours and high levels of suicidality. It is important understand the barriers which prevents homeless people who have ARBD or have experienced trauma from having their needs met.

Unresolved trauma often plays significant role in a person’s engagement with support services. We have discussed how traumatic events can result in complex mental health problems, difficulty regulating emotional responses and the development of negative views of oneself and the world. Consequently, people have problems developing/maintaining relationships and demonstrate “challenging” behaviours as a coping mechanism. Within services, these people are often unhelpfully defined as ‘hard to reach groups’, whereas more focus should be on the underlying roots of the disengagement. It is clear there is a vicious circle between trauma and homelessness. Trauma drives homelessness and homelessness can increase traumatic exposure. Trauma drives social difficulties and mental health problems which can cause homelessness and addiction.

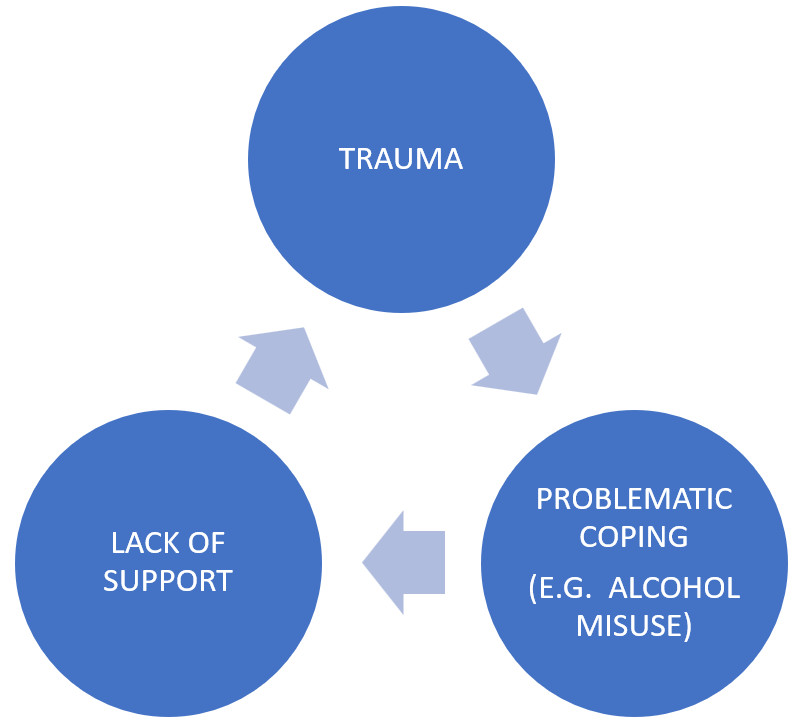

The Problem Triangle

ABRD also creates many barriers to a person engaging and accessing support/treatment from services. We have discussed the impact of cognitive impairments, physical health problems, stigma and mental health associated with alcohol misuse. The impact of ARBD on a person’s memory, reasoning, impulse control, reduced insight and planning makes it very difficult to convince them to stop drinking or engage with treatment/support. These problems are often further compounded by the effects of alcohol withdrawal, the use of alcohol to self-soothe and when a person is surrounded by social circles that drink.

Current support services are not designed to support the needs of those with ARBD which significantly increases the risk of relapse and disengagement. This lack of understanding and awareness of the needs of those with ARBD is reflected across many services including mental health, addiction, homelessness and physical health. In addition, there is a lack of defined pathways available for ARBD treatment which further exacerbates problems surrounding this area. People with ARBD can present with complex needs which impact multiple levels of their functioning. The prevalence of co-morbidities in those with ARBD means a multi-agency approach is required when providing treatment. Unfortunately, ARBD is associated with significant relapse and mortality rates, however treatment is often effective if it is delivered in the context of a person’s multiple complex needs, with up to 75% of people being able to recover and live successfully in community-based settings.